-

Informed Consent &

Malpractice -

Employment Litigation

ADA - Disability - Sexual Misconduct

Discrimination - Worker's Compensation -

Emotional &

Physical Damages

Conscious Pain & Suffering

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Neuropsychiatric Autopsy - Standards for Experts

-

Product Liability

Medical Devices & Pharmaceuticals

Toxic Tort -

Criminal Justice &

Public Safety

Diminished Capacity - Drug Addiction

Competency to Confess

Death Penalty Mitigation

Workplace Safety - Family & Custody Issues

-

Testamentary &

Contractual Capacity -

Professional &

Organizational Ethics

Patient Care - Managed Care - Privacy -

Psychoanalysis &

Cultural Perspectives -

Loading

Recognizing posttraumatic stress

When your patient seems depressed or anxious, consider posttraumatic stress

disorder in the differential.

The diagnostic guidelines are newly revised—and broadened.

Harold J. Bursztajn, MD; Paramjit T. Joshi, MD; Suzanne M. Sutherland, MD; David A. Tomb, MD

Article Consultants

Harold J. Bursztajn, MD, is Associate Clinical Professor of Psychiatry,

Harvard Medical School, Boston; and Co-Director, Program in Psychiatry

and the Law, Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Cambridge.

Paramjit T. Joshi, MD, is Associate Professor of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Suzanne M. Sutherland, MD, is Clinical Associate Professor, Departments

of Psychiatry and Family Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham,

N.C.

David A. Tomb, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry,

University of Utah School of Medicine Salt Lake City.

Symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are described in literature from as far back as ancient Greece. As recently as World War II, the syndrome was considered a neuropsychiatry reaction to combat stress and called shell shock, traumatic war neurosis, or combat exhaustion. Today, however, the diagnosis is applied broadly to the development of multiple affective, cognitive, behavioral, and identity reactions to any number of traumatic life experiences, including accidents; natural disasters; acute illnesses; acts of terrorism; physical, sexual, or psychological abuse; and wartime stressors (see Table 1, page 42). PTSD can also occur in persons who provide care to trauma victims, such as police officers, fire fighters, and health care personnel.

The disorder has provoked controversy and lends itself to exploitation, but it is genuine when accurately diagnosed. PTSD is considered among the most common of psychiatric disorders and affects all segments of the population.

Diagnostic Criteria

In 1980, when the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) was published by the American Psychiatric Association, PTSD was classified as one of the anxiety disorders. Previously it had been considered an expression of other psychiatric disorders. The decision to give PTSD a category of its own was supported in part by the pervasiveness of delayed stress reactions in veterans of the Korean and Vietnam wars. The next revision, DSM-III-R (1987), defined the traumatic stressor as one that "is outside the range of usual human experience and which would be markedly distressing to almost anybody." [1] Symptoms were organized under reexperience, avoidance, and increased arousal and had to persist for at least one month.

The DSM-IV definition

The most recent revision of the manual, DSM-IV, was published in 1994 and further Adapted with permission from Horowitz MJ, Bonanno GA, Holen A: Pathological grief Diagnosis and explanation Psychosom Med 1993,55:260-273. revises the classification. The diagnosis of PTSD now depends on specific features of the clinical presentation in addition to the nature of the external stressor.

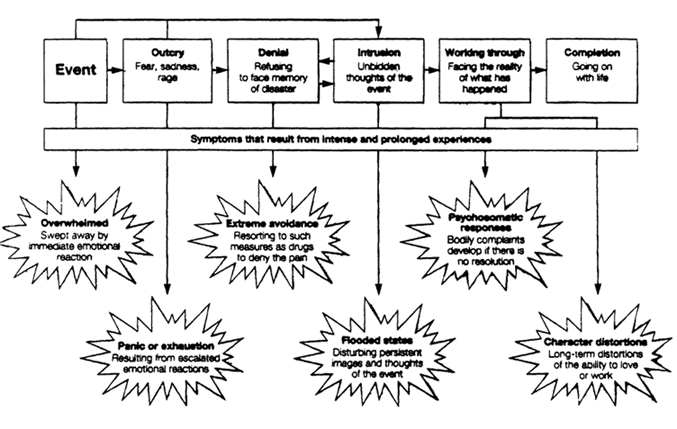

The traumatic event is the gatekeeper to PTSD: The patient must have suffered or witnessed an event "that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury" or "a threat to the physical integrity" of the self or others; the patient's response must have included "Intense fear, helplessness, or horror" [2] DSM-IV broadens the definition of the event and shifts the emphasis from its severity to the patient's reaction to it (see Figure 1). So persons who have had extreme reactions to some common events and those who have merely witnessed excruciating trauma are now included. The increased subjectivity of this broadened approach to diagnosing PTSD has generated controversy.

Figure 1 The response to stressful events may include the symptoms illustrated in this model of pathologic grief, which is similar in some ways to posttraumatic stress disorder. Each phase of working through trauma is accompanied by characteristic symptoms. Many patients do not proceed straightforwardly from one phase to another, however, so the symptoms that accompany various phases may occur simultaneously.

According to DSM-IV, a patient with PTSD must persistently reexperience the traumatic event. Avoidance of stimuli suggestive of the trauma and a general emotional numbing must be present. There must also be periods of dramatic and disruptive arousal. DSM-IV stipulates that the symptoms of avoidance, numbing, and increased arousal cannot have been present before exposure to the trauma, must endure for more than a month, and must cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment.

Reexperiencing the trauma can occur in various ways, but one or more of the following symptoms must be present for a diagnosis of PTSD:

- Recurrent and intrusive distressing recollections or dreams about the event

- Feeling as if the traumatic event were recurring, such as through hallucinations and dissociative flashbacks

- Intense psychological distress or physiologic reactivity when exposed to a cue that symbolizes the event, such as a burning building.

Avoidance can take the form of trying to circumvent thoughts, feelings, or conversations or activities, places, or people associated with the trauma. Amnesia about an important aspect of the event may occur. Numbing is indicated by markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities. The patient may feel detached and unable to feel emotions and have a sense of a foreshortened future. Sleep disturbances, concentration problems, hypervigilance, irritability, and exaggerated startle response all may be symptomatic of the increased arousal and anxiety syndrome, but two or more of those symptoms have to be present.

The disorder is considered acute if symptoms last less than three months and chronic if they last three months or longer. PTSD is considered to be delayed if symptoms begin more than six months after the event. A child's response to a traumatizing event is generally different from that of an adult. Disorganized, agitated behavior and repetitive play may express themes or aspects of the event, but the child does not recognize their significance. Dreams may contain frightening content, but children often do not associate that content with the traumatic event.

| Table 1 PTSD: Symptoms and manifestations |

| Cognitive symptoms |

| intrusive memories; memory impairment; trouble concentrating, inattentiveness; self-criticism; worry, distrust of others; anticipations of misfortune |

| Behavioral and pysiologic symptoms |

| Hyperalertness, impatience; insomnia, nightmares; palpitations, hyperventilation; trembling, faintness; numbness, withdrawal; nausea, diarrhea, headaches; compulsive, repetitive acts; angry outbursts |

| Affective symptoms |

| Emotionally reliving the event; irritability, anger; crying, sadness; guilt, low self-esteem; loss of control |

| Identity changes |

| Sense of foreshortened future; discontinuity from the past: alienation from self, others, work; sense of pervasive unreality; feelings of inadequacy, unworthiness |

Acute stress disorder

A phenomenon long associated with the development of PTSD, acute stress disorder has acquired the status of a separate anxiety disorder in DSM-IV. Acute stress disorder's symptoms must occur and resolve within four weeks of the traumatic event. The diagnosis is changed to PTSD if symptoms persist longer and meet other criteria. Patients suffering from acute stress disorder can be treated palliatively with an antianxiety agent or antidepressant.

Assessing Risk

Not everyone exposed to a traumatic event goes on to develop PTSD. Response to trauma is determined by multiple factors. The severity and duration of the traumatic event affect the likelihood of developing PTSD, as do the person's reaction and predisposition. People who were in a place they believed to be safe when the trauma occurred are more likely to develop PTSD. For example, a woman who is raped in her apartment is more vulnerable to PTSD than one who is raped on a street she knew to be dangerous.

| The legacy of undiagnosed "combat stress" |

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often presents with nonspecific or secondary symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or substance abuse. Countless war veterans have suffered with the undiagnosed disorder for many years, as illustrated in the following vignettes.

|

Pretrauma and posttrauma risk factors

The severity and chronicity of PTSD symptoms vary considerably from person to person. Emotional processing of the traumatic event interacts with factors such as predisposition and care following the trauma. Pretrauma risk factors include previous psychiatric condition, especially conduct disorder; family psychiatric history, particularly anxiety disorders, depression, and alcoholism; personality characteristics such as neuroticism and introversion; personality disorders, especially antisocial and narcissistic sub-types; and youth, low intelligence, poor education, low socioeconomic status, limited coping ability, early familial dysfunction, and limited social supports.

Posttrauma risk depends upon the quality of debriefing and intervention immediately following the trauma. The earlier the patient receives effective intervention, the more likely that the neurobiology changes associated with PTSD can be reversed. In a study of survivors of a ferry boat disaster, experiences preceding the disaster and crisis support following it were found to be the two best predictors of the survivors' intrusive PTSD symptoms. [3]

Programming the CNS

Evidence of an acute stress reaction is not required for the later diagnosis of PTSD, but such a reaction can be considered a risk factor as it indicates that the triggering event is traumatic. Panic and elevated pulse rate and blood pressure accompany the prompting of the sympathetic nervous system to overreact. The more trauma someone experiences, therefore, the more susceptible that person becomes to PTSD.

There is also a relationship to events occurring in the future. PTSD is more likely to develop after trauma later in life if a prior trauma occurred. For example, the PTSD symptoms associated with an early childhood trauma may not surface until a time of increased stress in the person's life or when a similar event, not necessarily traumatic, occurs. The combat veteran who suffered physical abuse during childhood is more likely to develop PTSD than a soldier who did not.

Negative psychological outcomes to war trauma are more likely to occur among soldiers who are exposed to gruesome experiences than among those who are not (see "The legacy of undiagnosed 'combat stress,'" page 43, and "Torture: A unique syndrome," page 48). In a study of Operation Desert Storm troops, previously healthy soldiers assigned to graves registration duty that involved handling human remains and processing dead bodies were at higher risk for developing mental disorders, specifically PTSD, than those not involved in such duties. [4] PTSD was frequently accompanied by depression, substance abuse, high levels of anxiety, and somatic complaints.

Childhood sexual abuse has been described as a risk factor for PTSD. A retrospective cohort analysis of the early developmental histories of maltreated children found that birth weight of less than 4.95 lb (225 kg) and behavioral problems, failure to thrive, and jumpiness in the first year of life increased vulnerability to PTSD, [5] The type of maltreatment is strongly related to the probability of developing the disorder, with sexual abuse and witnessing domestic violence emerging as significant predictors. Gender was not a significant factor.

Medical and psychiatric comorbidity

PTSD may increase the risk for other psychiatric illnesses or for physical illness. In turn, the symptoms of PTSD can be brought on or worsened by the stress of an illness or its treatment. Sedative-hypnotics prescribed for insomnia, for example, may contribute to behavioral disinhibition, and sympathomimetics given for asthma may heighten anxiety. The regimented order of a hospital setting may trigger disruptive associations.

Comorbidity with anxiety or panic disorders, depression, or dysthymia is common. Simple or social phobias, personality disorders, and somatoform disorders are also associated with PTSD as coexisting conditions. Psychosis can be a predisposing factor as well as a complication of PTSD. The primary care physician treating a patient with a chronic delusional disorder or paranoid schizophrenia should be alert to the possibility of symptoms worsening dramatically if a trauma occurs. The psychoses may themselves be predisposing factors to feelings of overwhelming helplessness and horror, which would magnify a relatively minor stressor into a major one and, possibly, produce PTSD.

| Torture: A unique syndrome |

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is frequently diagnosed in persons who have been tortured, but some critics think that the diagnostic formula in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV, Fourth Edition, is too limited to reflect the suffering associated with torture and that PTSD following that stressor is a unique syndrome. The authors of a report on a study of survivors of torture in Turkey concluded that three factors affect the degree of psychopathology in survivors of torture:

The torture victim with PTSD has a sense of personal humiliation and mistrusts friends, family, community, and institutions. The objectives of torture are to humiliate and devastate self-esteem and to confuse the victim's values. The torturer has close, personal, repeated contact with his prey. Victims are often made to choose between two torturers—the "good" one and the "bad" one—and the experience has a psychologically crippling outcome. Interventions different from those used with other patients with PTSD may be needed for torture victims. Psychotherapy must focus on issues of self-esteem, trust, denial, grief, and survivor guilt. The symptoms can be treated by cognitive and behavioral strategies; then the involvement of spouses and other family members should be enlisted so that the impact of the trauma on them can be minimized. In addition, strategies for enhancing social support are needed to minimize depression and anxiety. Basoglu M, Paker M, Ozmen E, et al: Factors related to long-term traumatic stress responses in survivors of torture in Turkey. JAMA 1994; 272 357-383. |

Evaluating The Patient

Patients sometimes experience guilt about surviving the traumatic event ("Why didn't I die instead?"). Some experts view this as an omission in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria that may be rectified in the next edition. Survivor guilt occurs in only 15% of cases of PTSD, but those tend to be the most serious cases. Many persons express shame about not being able to deal with the traumatic event, thereby making it difficult for them to openly acknowledge their symptoms.

The differential diagnosis

Detection of PTSD would proceed smoothly if the patient candidly and explicitly described the stressor and the intrusive memories or dreams. But the patient with PTSD may have symptoms characteristic of another anxiety disorder, and those may be the prominent features of the clinical presentation. PTSD symptoms may not become detectable until later.

In addition, PTSD may be accompanied by anhedonia and is often misdiagnosed as depression. The patient might say, "I'm not happy. I'm irritable all the time. My family says I'm hard to live with. I have trouble sleeping and can't concentrate while awake." Those are symptoms of depression, but they are also symptoms of PTSD. It is important to probe further: "Are you having bad dreams? Do those dreams remind you of something difficult that happened to you? Did something happen that you can't seem to get out of your mind?" In most cases, those traumatic experiences won't be related unless specifically solicited.

Ferreting out the stressor

The expression of symptoms is often culturally dependent, and the avoidance and numbness characteristic of PTSD may further cause patients to avoid communicating symptoms or become numb to them. Some patients may feel embarrassed to expose the stressor, particularly when it involved sexual or spousal abuse, or they may fear that they will appear "crazy" if they report flashbacks.

Establish an atmosphere where the patient feels safe in communicating thoughts and feelings. If your attempts to expose the stressful experience are unsuccessful, ask, "Have you had any life experiences that didn't especially bother you but that other people might find stressful?" Phrasing the question this way allows the person to continue denying the traumatic nature of the experience but still describe a history of trauma that may be manifesting itself silently. Events that cause PTSD are painful to hear, and physicians often must monitor their own inner reactions so as to avoid making distancing or patronizing comments. Try to listen empathically while providing an emotionally safe environment for the patient.

Childhood sexual abuse

Patients with PTSD who were abused in childhood often feel overwhelming, uncontrollable rage. They may be abusive to their own children while in enraged states. Recognition, in addition to preventing comorbidity and enabling proper treatment, may prevent further suffering.

Screening should be done routinely since secrecy is the legacy of childhood sexual abuse. Failure to ask patients about childhood trau- mas conveys the perception that such traumas are unimportant and unrelated to current PTSD symptoms. A tone of caring and respect can be conveyed in questions such as, "Did anyone ever touch you in a way that made you uncomfortable? Were you afraid of anyone in your family? How was anger dealt with in your family?"

A negative response does not rule out the possibility that abuse occurred; the question can be asked again in a different context. A positive response must be evaluated carefully; be certain it is not coerced. A response revealing sexual abuse may be accompanied by anxiety. The physician should help the patient stay grounded in the safety of the present.

Identifying the malingerer

PTSD is a controversial diagnosis because of the possibility of exploitation. If the words "service-connected" are attached to a PTSD diagnosis, the veteran has increased access to medical benefits. Some Veterans Affairs doctors are suspicious that compensation- or treatment-seeking people may research PTSD and then claim to have the symptoms. Factitious PTSD may also occur in the civil or criminal court system (see "PTSD: Medicolegal implications," page 52). For the most part, patients with genuine PTSD

- Attempt to minimize the association between the symptoms and the traumatic event

- Blame themselves for the event's occurrence

- Initially deny the emotional impact of the event

- Are reluctant to recount any details of the stressor

- Feel angry at themselves for being unable to overcome symptoms.

Management

Early recognition of PTSD is essential. Treatment should be started as soon as feasible after the stressor to prevent the condition from becoming chronic (lasting more than three months) and causing personality changes or other psychiatric or physical disorders. No one type of management has been shown to be consistently effective, probably because the underlying pathophysiology of PTSD is not completely understood.

| PTSD: Medicolegal implications |

Since its official recognition as a psychiatric diagnosis in 1980, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has become an important factor in civil and criminal trials. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R), the precipitating stressor was defined as one "that is outside the range of usual human experience and that would be markedly distressing to almost anyone." However, in the 1994 revision, DSM-IV, the definition rests upon an event that "involve[s] actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of oneself or others" and the person's response to that event. This more subjective definition opens the way for frequent claims of PTSD as a form of severe emotional injury in civil matters and as a defense in criminal matters. Three other recent developments portend an even more prominent role for PTSD in the courtroom: The discovery of a physiologic basis for persistent memories of terrifying experiences, validating the claim that the disorder can be a lifelong condition: the psychophysiologic laboratory demonstration of PTSD as a condition with emotionally and physically distressing symptoms; and the inclusion of an enduring personality change after a catastrophic experience as an identifiable disorder in the International Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (ICD-10) of the World Health Organization. [1-3] Forensic psychiatric evidence has gained such prominence as an asset in litigation that an attorney who fails to present the evidence may be vulnerable to a charge of malpractice as "ineffective assistance of counsel." [4] Harold J. Bursztajn, MD, a practicing forensic psychiatrist and one of the consultants for this article, served as an expert witness in the following case that demonstrates how PTSD can be shown to be a form of emotional injury in a civil trial: A New Hampshire couple brought suit against Kmart Corporation for emotional damages resulting from an incident of alleged false arrest for shoplifting. The plaintiffs' attorney contended that the woman charged was from a conservative, family-oriented background where honesty was held in high regard. Dr. Bursztajn testified that "the event of [the plaintiff's] apprehension and imprisonment caused her to suffer PTSD that manifests itself in the following respects: (1) [she] experiences recurrent and intrusive recollections of the event, (2) she has recurrent dreams of the event that awaken her, (3) whenever she attempts to describe the event, she becomes frightened and overwhelmed, and (4) she has withdrawn from participating in her children's school activities and has grown detached from her husband... ." [5] The jury awarded $1 million to the plaintiffs: $5,000 for psychiatric services and $995,000 for psychological injuries. Another $100,000 was awarded to the husband for loss of consortium. Although the trial court set aside the awards as excessive, it found a "substantial body of evidence" in favor of compensating the woman for her psychological trauma, in other kinds of civil cases, those involving acts of violence and sexual abuse and harassment, PTSD can be a powerful factor in substantiating damage claims. PTSD is also often cited as a support for defense claims in criminal matters where the defendant's state of mind is rased as an issue, as in battered-wife syndrome claims. In addition, PTSD can be cited to reduce the severity of charges—such as from premeditated murder to manslaughter—or as a major mitigating factor. On January 18,1995, a New York City court convicted a Lebanese immigrant of firing bullets into a van containing Hasidic students, killing one and injuring others. The young man had been in the militia since age 9 during the civil war in Lebanon and had experienced serious war trauma. His defense team testified that his actions on the day of the shooting were linked to his PTSD. They said that he had a flashback and believed the students in the van were attacking him, based on his recollection of the massacre of Muslim worshippers in Hebron, Jordan, by a Jewish settler last year.

|

A multifaceted approach

PTSD is remarkably underdiagnosed by primary care physicians, and yet they are likely to see the patient with PTSD first. Once identified and stabilized, the patient is best treated by a psychiatrist. Group, individual, and family psychotherapy is generally combined with pharmacologic intervention in PTSD (see "Relaxation as adjunctive treatment"). Psychotherapy attempts to make conscious the sources of apprehension provoked by the triggering event or events and establishes a connection between past events and current symptoms.

Before undergoing psychotherapy, patients with PTSD typically believe that the event they experienced is so awful they cannot think about it; they believe they cannot even talk about it because knowledge of it would harm people who listened. Patients shut off their feelings about the event. By encouraging talk about the experience and listening attentively, the psychotherapist demonstrates that the event can be dealt with and that the patient can safely relate details. The healing process comes from communicating the memory of the trauma to another person and experiencing the memories and emotions together. This develops a cognitive understanding of how the outside world relates to the trauma. Interpersonal remembering, when it occurs in a supportive framework, can eventually take the place of reliving the trauma.

| Relaxation as adjunctive treatment |

Self-hypnosis, diaphragmatic breathing techniques, biofeedback, and cognitive and visualization processes can be used to induce a relaxation response in chronically stressed people, including patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Reenie Davison, MA, a relaxation therapist and director of the Stress Management Program at the Martinez Veterans Affairs Mental Health Outpatient Clinic in Martinez, Calif., employs ail of these. With her help, muscles relax, heartbeat slows, and breathing deepens. "Patients with PTSD carry severe and chronic tension patterns in their upper bodies because they are constantly defending themselves against their subconscious," Davison says. "Relaxation therapy teaches them how to feel comfortable inside their own skins." Her method is noninvasive and allows memories to remain in the subconscious; it is most useful to patients who are concurrently processing the traumatic material through psychotherapy or who have had the emotional pain partially blunted through parmacologic intervention. "At first Vietnam vets may have a paradoxical response to relaxation techniques. Instead of exhibiting the relaxation I expect, they may panic and experience increased anxiety," Davison says. This happens because in order for them to enter a relaxed state, they have to approach their subconscious where traumatic memories are stored. "Sometimes I will instruct a Vietnam vet to visualize going down a pleasant country road and coming upon a peaceful scene in nature," Davison explains. "What he sees when he gets there, however, is his personal horror: torture, dead bodies and body parts, the terror of ambush and crashing bombs." Flashback implodes, the subconscious becomes a terrifying environment, and panic sets in. To deal with the paradoxical response, the therapist slows down the relaxation induction by having patients go through the process with eyes open or while walking. The technique keeps them in touch with their outer reality and increases their sense of control and safety. |

Pharmacologic intervention

While most patients benefit from talking through the trauma until it becomes less frightening, some lack the strength to cope with the massive, essential damage they have suffered. For those patients, working through the traumatic event is not recommended without benefit of medication. PTSD brings about biologic changes affecting the locus coeruleus, the sympathetic nervous system, and the amygdala. When medication is given in preparation for psychotherapy, the responses symptomatic of the disorder are dampened, and patients feel able to watch and talk about the intrusive images of their trauma without feeling overwhelmed by them.

In addition to facilitating therapy, drug treatment can be useful in managing PTSD symptoms by providing relief from distressing and intrusive nightmares, flashbacks, and images and reducing the intense psychological and physiologic distress caused by reminders. Drugs alleviate depression, anhedonia, and suicidal tendencies and reduce the generalized autonomic hyperarousal, irritability, aggression, insomnia, and startle response.

Tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be effective for most people with PTSD. [*] While the use of benzodiazepine anxiolytics in this population is controversial because of the possibility of dependency, the longer-acting drugs in this class can be particularly effective for the hyperarousal symptom.

All classes of antidepressants help with nightmares, other sleep symptoms, and intrusive daytime thoughts. Depressive symptoms respond to all antidepressants, while the SSRIs help with withdrawal, estrangement, and numbing symptoms and help patients to experience rather than deny their emotions. Fluoxetine HC1 was studied in PTSD and found to be particularly effective in previously untreated patients, including those with co-morbid major depression. [*,6] Propranolol HC1 for physiologic reactivity and stabilizing drugs such as carbamazepine are possibilities as well. [†]

If a patient is not responding to antidepressant medications and has dissociative symptoms such as extreme terror and flashbacks, β-blockers [‡] and MAOIs can help. MAOIs should be prescribed with caution because they require adherence to a restricted diet and cause side effects such as troubled sleep, weight gain, and memory and concentration problems.

Patients with disruptive responses to life event3 often are mislabeled as schizophrenic when in fact they are having PTSD-related dissociative or flashback events. They may even be labeled atypically psychotic and be given neuroleptic agents. Referral should be made to a psychiatrist who can determine whether the patient is psychotic or dissociating. Be aware that drug treatments tend to provide less than total recovery in most cases, particularly when the symptoms are long-standing. Responses may take many weeks or months.

The importance of rapid treatment

If treatment for PTSD is delayed or denied, as was the case for innumerable combat veterans and other trauma victims before official recognition of the disorder, anxiety can become chronic and disabling. The patient can develop phobias or begin to self-medicate with alcohol or other drugs. The worsening of depression, panic, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can be a significant complication of untreated PTSD. If medications are prescribed for depression or OCD but the PTSD is not treated, the underlying stressor will not be exposed; some symptoms may be eased, but the PTSD will not be resolved.

As recovery progresses, the brain frequently protects the patient from severe trauma by allowing some amnesia to remain. Complete remembering of the traumatic experience should not be forced. Psychotherapists allow the patient to set the pace. Some events may be too traumatic. Often bits and pieces come back over time; sometimes the whole experience reemerges.

PTSD and substance abuse

Among Vietnam veterans with PTSD, 60-80% exhibit concurrent substance abuse or dependence. [7] A variety of complex interactions before, during, and after the trauma lead to PTSD, and even more factors come into play to produce the compound diagnosis. Most experts agree that PTSD develops first and alcohol or drug addiction arises secondarily, sometimes as self-medication.

Treating substance abuse does not resolve the symptoms of PTSD. Trying to enforce sobriety before beginning treatment for PTSD is impractical because significant psychiatric symptoms reduce the efficacy of treatment for addiction. Patients with a dual diagnosis have even more difficulty achieving and maintaining sobriety than chemically dependent persons without PTSD; withdrawal from the substance may itself trigger a conditioned response associated with PTSD symptoms.

Successful treatment of the concurrent disorders requires stabilization, control of PTSD symptoms within 2-3 weeks, and simultaneous therapy for the substance abuse. The patient needs to learn to cope with and work through difficult feelings generated by sobriety-induced awareness and to develop self-understanding. Combining group and individual psychotherapy with aspects of long-term 12-step programs has been shown in several studies to relieve both PTSD symptoms and addictive behavior. Relapse-prevention techniques are applicable to the PTSD and the substance abuse; aftercare should impact as little as possible on daily life.

Referring the patient

Many patients refuse referral for psychiatric confirmation of the PTSD diagnosis or for psychotherapy. They may see referral as a blow to self-esteem or a personal failing. A number of factors can enter into that perception, and the PTSD itself may fuel the patient's objection. Patients may not understand the effect of the psyche on physical symptoms. They may feel rejected by the referring primary care physician. They may fear the social stigma attached to psychiatric illness.

To facilitate acceptance of a psychiatric referral, first assure the patient that a positive diagnosis of PTSD has been made. Explain that your medical workup was thorough and has ruled out any underlying physical conditions that may be creating or amplifying symptoms. The patient must be convinced that no stone has been left unturned. Include family and friends in counseling sessions. Pre- scribe an anxiolytic if the patient needs psychopharmacologic intervention until a more definitive psychiatric evaluation can be done.

Suggest the referral in a straightforward manner, and explain your reasons. Observe the patient for signs of anger or apprehension. The goal is not merely to place the patient in the psychiatrist's office, but to help the patient go there with an open mind. The decision cannot be rushed; it may take a few office visits for the idea to be assimilated.

Carefully chosen words are necessary when confronting a patient's fear of social stigma and bruised self-esteem. Assure the patient that you will continue to provide care. Validate the patient's emotions with empathic statements such as: "You must feel I'm overreacting by sending you to a psychiatrist when the pain you're feeling is obviously real. But I need the advice of an expert." This places the responsibility for the psychiatric referral on the physician. Offer reassurance that whatever family and friends may say or feel about the patient's going to a psychiatrist, you don't share their perception and the patient needn't either.

Prepared by Dorothy L. Pennachio

Senior associate editor

References

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition. Revised. Washington, DC American Psychiatric Association, 1967.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Fourth Edition. Washington DC. American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

- Joseph S, Yule W, Williams R, et al: Correlates of post traumatic stress at 30 months: The Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. Behav Res Ther 1994;32:521-524.

- Sutker PB, Uddo M, Brailey K, et al: Psychopathology in war zone deployed and nondeployed Operation Desert Storm troops assigned graves registration duties. J Abnorm Psychol 1994;103:383-390.

- Famularo R, Fenton T. Early developmental history and pediatric posttraumatic stress disordar. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1994;148:1032-1038.

- van der Kolk BA, Dreyfuss D, Michaels M, et al. Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:517-522.

- Kofoed L, Friedman MJ, Peck R. Alcoholism and drug abuse in patients with PTSD. Psychiatr Q 1993;64(2):151-171.

- *Some agents may not be FDA-approved for PTSD/anxiety disorders.

- † Unlabeled uses.

- ‡ Unlabeled use; concurrent use of B-blockers and MAOIs may cause bradycardia.

Suggested Reading

- Allodi FA: Assessment and treatment of torture victims: a critical review. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991;179:4-11.

- Gunderson JG, Sabo AN: The phenomenological and cenceptual interface between borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:19-27.

- Hamner MB: Exacerbation of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms with medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1994;16:135-137.

- Kantemir E: Studying torture survivors: An emerging field in mental health. JAMA 1994;272:400-401.

- Mellman TA, Kulick-Bell R, Ashlock LE, et al: Sleep events among veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:110-115.

- Langone MD (ed): Recovery from Cults: Help for Victims of Psychological and Spiritual Abuse. New York, WW Norton & Co. 1993.

- Terr L. Unchained Memories. New York, BasicBooks, 1994.