-

Informed Consent &

Malpractice -

Employment Litigation

ADA - Disability - Sexual Misconduct

Discrimination - Worker's Compensation -

Emotional &

Physical Damages

Conscious Pain & Suffering

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Neuropsychiatric Autopsy - Standards for Experts

-

Product Liability

Medical Devices & Pharmaceuticals

Toxic Tort -

Criminal Justice &

Public Safety

Diminished Capacity - Drug Addiction

Competency to Confess

Death Penalty Mitigation

Workplace Safety - Family & Custody Issues

-

Testamentary &

Contractual Capacity -

Professional &

Organizational Ethics

Patient Care - Managed Care - Privacy -

Psychoanalysis &

Cultural Perspectives -

Loading

The Multidimensional Assessment of Dangerousness: Competence Assessment in Patient Care and Liability Prevention

Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law, Vol. 14, No. 2,1986

Thomas G. Gutheil, MD; Harold Bursztajn, MD; and Archie Brodsky, BA

Drs. Gutheil. Burwtajn, and Brodsky are afiliated with !hi Program in Psychiatry and the Law. Massachusetts Mental Health Center and Haward Medical School. Boston. MA. Address reprint requests to Dr. Gutheil. 74 Fenwood Rd., Boston. MA 02115.

We offer a multidimensional model for assessing dangerourness of patients in relation to their competence to engage in informative dialogue with clinicians. This model, though based on clinical considerations, may offer some degree of liability protection. Current clinical and legal trends are reviewed as they bear upon this determination.

Clinicians attempting to assess and then predict dangerousness in psychiatric patients have approached the task with serious reservation [1-3] based on the clear predictive limitations demonstrated by empirical studies. [4,5] Empirical findings demonstrate relatively low accuracy of prediction and low foreseeability of dan- gerous acts by patients. Nevertheless, civil courts in some recent case [6-8] and even the Supreme Court [9] have continued to act as though dangerousness were clearly predictable. Proceeding from this premise, courts then rule as though failure to predict and then to prevent dangerousness constituted negligence. [10] The result has been a marked expansion of liability for clinicians. [11]

Determination of liability is subject to numerous variables—nature of case, publicity given to the dangerous act, quality of lawyers involved, expert witness testimony, wisdom and attitude of the judge, etc.—that would appear to defeat any attempt to derive some guidelines for clinicians. We would like to suggest, however, that increased understanding of one legal current may actually aid the clinician in decreasing liability risk and in improving patient assessment. To understand the point at issue, we must first identify a latent assumption in the law.

Legal Views

In cases involving liability for suicide, [12] courts have often tended to view suicidal mental patients as globally incompetent, often without any evidence for this view. While the courts in question often appear to be unaware that this process is occurring. the patient is essentially portrayed as a child in the hands of parentally responsible clinicians. [13] In such a characterization. the "child-patient" cannot really be seen as responsible for his/her actions, since he/she is "just a child": instead, the "parent-clinicians" (the responsible adults) must be held responsible or, in this case, liable (note, parenthetically, the paradox that, when the issue is the right to refuse treatment instead of malpractice, similar patients have been portrayed as globally competent!).

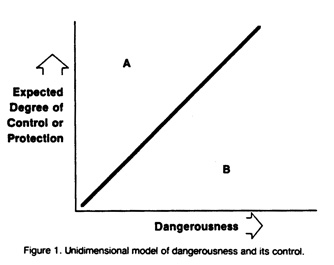

Starting from the premise of global incompetence, courts then employ a unidimensional model of dangerousness and its control (Fig. 1). The degree of control over or restraint of the patient expected to be exercised by the clinician varies directly and simply with the degree of patient dangerousness to self or others; greater danger calls for greater controls. Within this model, if the clinician exerts too much control relative to the danger (point A), the patient's civil rights may be seen as compromised; if too little control is exerted (point B), the clinician may be deemed to have been negligent if the patient harms someone else or himself/herself. As earlier noted,the clinicians appear in a number of court decisions to be the only actors: the patient is inert. Clearly, in any legal case this model operates by hindsight, with the attendant illusion of certainty and conviction of accuracy inherent in that vantage point. [12]

Some courts, however, have grasped the important distinction, usually intuitively understood by clinicians, between outpatients and inpatients and the varying degrees of control that can be exercised over these disparate groups. Outpatients are viewed as more broadly competent for their actions; hence. clinician control is diminished and the resulting liability when bad results occur is decreased. A suicide liability case [14] recently made this explicit, capturing an important clinical refinement in the assessment of the suicidal patient (one form of dangerousness). In a presumably competent outpatient, the patient's suicidal intent itself, not medical negligence, was deemed to be the causal factor in the suicide; hence, the clinician was not liable.

Proposed Model

A model that hews closer not only to actual practice but to clinical applicability—and perhaps to liability reduction—is the multidimensional model pictured in Figure 2, designed by members of the Program in Psychiatry and the Law at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center. This model is based on the clinical observation that two essential elements of clinical work, informed consent and the therapeutic alliance, [15] assume and require some level of patient competence: specifically, the patient's preserved ability to engage in a dialogue with the clinician to weigh the risks and benefits of his or her actions—this weighing constituting a reasonable definition of socially valid responsibility. Such capacity to engage in this process with another human being is essential for the sort of deliberate, mature decision making which represents the patient's competence to inform the clinician of potential self-harm or violence or, comparably, competence to handle responsibly a pass or some other increase in freedom.

The form of competence here envisioned begins with the clinician conveying to the patient, "I can only help you if you level with me"; "I can't know what you are concerned about unless you tell me in words or actions"; and similar communications. The clinician then determines whether the patient understands this issue. This determination is essentially identical to deciding if the patient is capable of informed consent; the documentation here might convey that the patient appeared to be capable, by specific assessment, to weigh the risks and benefits of giving or withholding information. Should the patient's assurances of safety later prove to be deceptions, the record will demonstrate that the patient could have revealed his/her destructive plan, but competently elected not to; the patient was not incompetent, so as to be beyond electing anything.

This approach is rooted solidly in clinical observation. For patients who are incompetent to participate as reliably in a decision-making alliance, the tie to the clinician (as both someone to live for and someone to inform about, say, homicidal or suicidal pressures or future plans) is not as available to aid in preventing those clinical states that lead to dangerous actions-states which represent greater risk in part just because the patient feels isolated in this way. Thus, assessing this specific competence has direct clinical utility in measuring the strength of the doctor-patient relationship as it relates to important judgments.

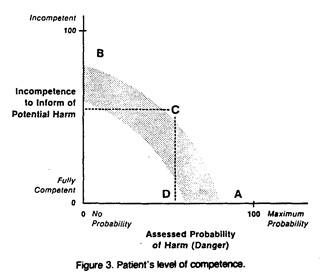

We define axes for both the staff's assessment of the patient's dangerousness (i.e., short-term dangerousness within the limits of clinical predictability) and the patient's level of impairment of competence to inform clinical staff about suicidality or danger to others. Patients in specific clinical states of varying dangerousness or incompetence may be "mapped" or located on this schema. Such "mapping," of course, is intended as an heuristic device; we cannot claim that incompetence can be precisely, quantitatively assessed, nor that assessment of danger and incompetence can be strictly biaxial or can be measured in comparable "units," implying that these two parameters necessarily have equal standing.

We can then identify two decision areas—the area of patient assumption of risk and the area of clinicians' assumption of risk; a border zone of negotiation and two boundary demarcations, the hospitalization threshold and the commitment threshold. Thus, although there are only two axes, a multidimensional model is produced.

The inner white area labeled "Patient Assumes Risk" represents a clinical state wherein the patient's level of danger and level of impairment of competence to inform are both low. A patient whose clinical condition can be described within this region is "his/her own master"—a responsible adult, despite the presence of mental illness. Here, the patient's own decisions should be respected and negotiations regarding expansion of liberties, privileges, and the like should take place within the parameters for informed consent; [15-18] the patient's participation and consent should be treated as valid. Many patients seen in practice, particularly those in the phases of recovery and on the verge of discharge, fall within this realm.

In contrast, patients whose level of assessed danger and/or whose level of incompetence locates them beyond the gray zone, in the outer white zone in Figure 2, are either too dangerous or too incompetent to make their own decisions as to their actions. Such patients require active, even unilateral, intervention by their caretakers; these interventions may take the form of legitimate constraints, restrictions, and substitute dedsion making (by a guardian, for instance).

Finally, the gray zone defines an area where further observation, data gathering, or negotiation with the patient and others should take place to "locate" the patient more precisely on this schema. This area is deliberately pictured as broad, in order to convey the idea that there is no "bright line" separating those clinical states where the clinician must "take over" from those in which the patient may safely act autonomously. Because this zone is also an area of uncertainty, close monitoring of patients "situated" in this region is clearly essential.

The two thresholds bounding this gray zone are straightforward. As either danger or incompetence increase, a patient may require hospitalization, preferably voluntary but negotiable; as danger or incompetence increase, the patient's condition may reach the threshold where involuntary commitment is required (Fig. 2).

The value of this multidimensional conceptualization of a patient's level of safety or danger is that it offers the clinician a surer sense of what is required, as well as a systematic, clinically usable framework within which to make difficult decisions that may have tragic outcomes. For example, a patient at A in Figure 3 is highly dangerous despite little competence impairment. Examples might include the violent psychopath, perhaps, or dangerous paranoid patient. The need for the clinician's control of the situation under these conditions is clear, no matter how "together" and "sane" the patient may appear. Comparably, the patient at B in Figure 3 is not acutely dangerous, but is so competence impaired as not to be able safely to make his/her own decisions: some aggressive, inarticulate patients might be located here. In such cases, again, the caretakers must accept their responsibilities.

To see the value of this schema in more problematic cases, consider the patient at C in Figure 3. The patient's moderate level of danger, when coupled—as it were, synergistically—with moderate incompetence, is just sufficient to require the caretakers to take the responsibility. An example would be a patient just beginning to recover from a violent acute psychotic episode, who has not fully reconstituted.

In contrast, a patient at D in Figure 3, although moderately dangerous, remains sufficiently competent to exercise judgment and thus to be expected to bear the responsibility for his/her actions, like the average citizen. Some impulsive borderline patients might fit this category. [19] In all of these cases, the clinician would retain the burden of actually performing and especially documenting the assessment of the patient's competence. Relevant data might include the patient's history of openness or guardedness, honesty or duplicity, ability to consider the value of informing caretakers of his/her intentions, and the like.

Discussion

This diagram is a heuristic model rather than a graph of empirical measurements; it is intended to offer a way of thinking about a complex subject. We propose that this schema permits more useful and accurate assessment of actual patient dangerousness and permits the clinician to determine more accurately when to intervene unilaterally and when to seek the patient's active participation in decision making through informed consent—improvements that clearly redound to the patient's benefit.

This framework holds additional value for liability prevention. If the patient's competence is documented and available in the chart for use in litigation it is more difficult for the court to portray the patient as a helpless, incompetent child under the exclusive control of the caretakers. Such a vision paints the clinician's actions as entirely detemerminative of any outcome, as though the clinician's actions (and, presumably, negligence) "caused" the dangerous act that led to the lawsuit. [20]

Conclusion

We offer a multidimensional model for assessment of dangerousness in relation to incompetence, based on theoretical considerations, clinical experience, and empirical study of decisions in legal cases. We suggest that this model offers a clinically useful guide for the clinician's approach to decision making with difficult patients. In addition, whereas legal outcomes can never be guaranteed because of the multiplicity of variables involved, this schema may offer some protection against inappropriate assignment of liability.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge our indebtedness to Ms. Elyse Littaye for assistance with the manuscript and to Dr. Philip Brown and Ms. Joyce Nevis-Olsen for valuable suggestions.

References

- Steadman HJ: Predicting dangerousness among the mentally ill: Art, magic and science. Int J Law Psychiatry 6:381-90, 1983

- Cocozza JJ, Steadman HJ: Prediction in Psychiatry: An example of misplaced confidence in experts. Soc Problems 25:265-76, 1978

- Carter CA: Some conditions predictive of suicide at termination of psychotherapy. Psychother Theory Res Pract 8:156-7, 1971

- Monahan J: The prediction of violent behavior: Toward a second generation of theory and policy. Am J Psychiatry 141:10-5, 1984

- Motto JA. Heilbron DC, Juster RP, Bostrom AG: Suicide risk assessment: development of a clinical instrument, in Proceedings of the Fourteenth Annual Meeting of the American Association of Suicidology. Albuquerque, NM, 1981

- Jablonski v. U.S., No. 81-5786 (9th Cir. June 14, 1983)

- Hedlund v. Superior Court of Orange County, 194 Cal. Rptr. 805 (Cal. 1983)

- Petersen v. Washington, 671 P.2d 230 (Wash. Sup. Ct. 1983)

- Barefoot v. Estelle, 103 S. Ct. 3383 (1983)

- Davis v. Lhim, 335 N.W. 2d 481 (Mich. App. 1983)

- Appelbaum PS: The expansion of liability for patients' violent acts. Hosp Community Psychiatry 35: 13-4, 1984

- Gutheil TG, Bursztajn H, Swagerty E, Brodsky A: Magical thinking in suicide litigation: I. Causality, modality and confusion in reasoning about negligence. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, Nassau, The Bahamas. October 24-28. 1984

- Gutheil TG: Malpractice liability for a patient's suicide. Legal Aspects Psychiatr Pract 1:l-4, 1985

- Speer v. U.S., 512 F. Supp. 670 (N.D. Tex. 1981)

- Gutheil TG, Bursztajn H, Brodsky A: Malpractice prevention through the sharing of uncertainty: Informed consent and the therapeutic alliance. N Engl J Med 311:49-51, 1984

- Gutheil TG, Appelbaum PS: Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1982

- Bursztajn H, Feinbloom RI, Hamm RM, Brodsky A: Medical Choices, Medical Chances. New York, Delacorte Press, 1981

- Bursztajn H, Gutheil TG, Hamm RM, Brodsky A: Subjective data and suicide assessment in the light of recent legal developments: II. Clinical uses of legal standards in the interpretation of subjective data. Int J Law Psychiatry 6:331-50, 1983

- Gutheil TG: Medico-legal pitfalls in the treatment of borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 142:9-14, 1985

- Gutheil TG, Bursztajn H, Hamm RM, Brodsky A: Subjective data and suicide assessment in the light of recent legal developments: I. Malpractice prevention and the use of subjective data. Int J Law Psychiatry 6:317-29, 1983