-

Informed Consent &

Malpractice -

Employment Litigation

ADA - Disability - Sexual Misconduct

Discrimination - Worker's Compensation -

Emotional &

Physical Damages

Conscious Pain & Suffering

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Neuropsychiatric Autopsy - Standards for Experts

-

Product Liability

Medical Devices & Pharmaceuticals

Toxic Tort -

Criminal Justice &

Public Safety

Diminished Capacity - Drug Addiction

Competency to Confess

Death Penalty Mitigation

Workplace Safety - Family & Custody Issues

-

Testamentary &

Contractual Capacity -

Professional &

Organizational Ethics

Patient Care - Managed Care - Privacy -

Psychoanalysis &

Cultural Perspectives -

Loading

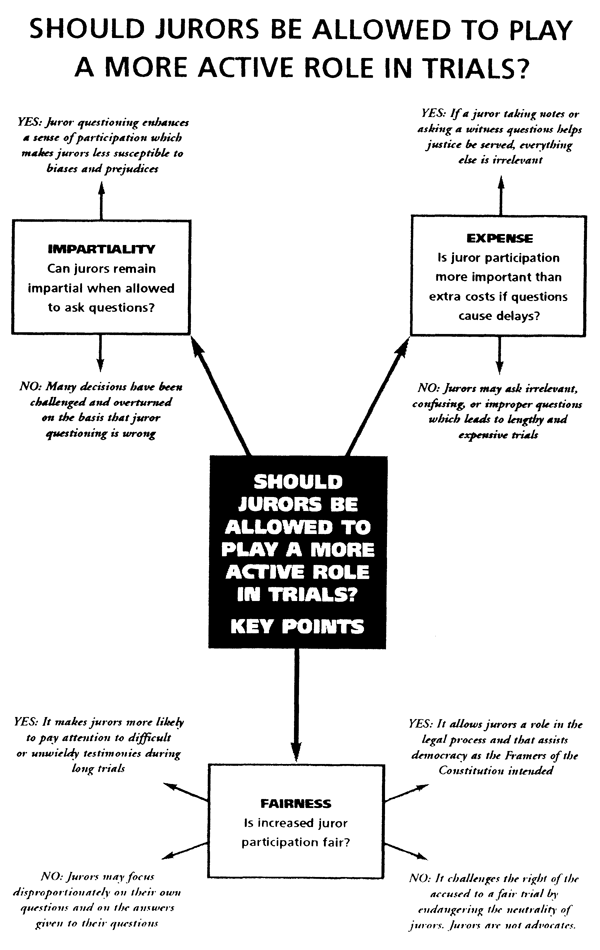

Should Jurors Be Allowed

to Play |

| Yes "Keeping A Jury Involved During A Long Trial" Forensic Psychiatry & Medicine: Trial Consulting and Forensic Psychiatry Harold J. Bursztajn, Linda Stout Saunders, and Archie Brodsky No From "The Current Debate on Juror Questions: 'To Ask or Not to Ask, That is the Question': 2. Biases" Chicago-Kent Law Review, Vol. 78, No. 3, 2003 Nicole L. Mott |

Introduction |

Jury service is a democratic way of giving citizens an opportunity to participate in the administration of justice. More than one million people serve as jurors in state courts each year. The Framers of the Constitution felt that juries, made up of ordinary citizens, were indispensable in acting as a check against the abuse of government officials. Trial by jury was the only right explicitly included in each of the state constitutions passed between 1776 and 1789.

Juries have traditionally been seen as a vital democratic institution because they allow citizens to engage in self-government. As the French social philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) stated. The jury is both the most effective way of establishing the people's rule and the most effective way of teaching them how to rule. In recent years, however, juries have been increasingly criticized for reaching unfair or unpopular decisions. Critics believe that more active jury participation would help prevent such outcomes. They claim that in many cases the court system and officials make it as difficult as possible for jurors to do their jobs. Jurors, they point out, are often treated with contempt, and lawyers and judges use legalese rather than concise, understandable language when explaining difficult concepts. Many judges also prohibit jurors from taking notes during trial; and while some allow jurors to ask questions, others forbid it completely Other critics argue that increasing juror participation in trials challenges the adversary system and allows jurors to move beyond their objective role as fact finders, thus challenging due process.

The issue of juror questioning lies at the heart of any discussion on jury participation. According to the state rules of procedure, most stales have allowed jurors to submit written questions to witnesses during court deliberations. This has expanded in recent years, and many courts now permit jurors to ask questions during, or after, a counsels presentation of evidence. But legal opinion is divided over whether juror questioning is a positive or negative process.

"The hallmark of the American trial system is the pursuit of truth.... [This] is attainable only if counsel successfully communicates evidence to the jury."

—Ohio Supreme Court (2000)

States usually fall into one of three categories when it comes to the subject of juror questioning. First are the states, like Mississippi, that "condemn" and "forbid" the practice. Second are those where it is not prohibited, but the practice is not usually allowed. Third are those states in which questions are permitted as long as they adhere to certain guidelines. Texas, Georgia, and Minnesota, for example, are among the states that do not allow questioning in criminal cases. Florida, Indiana, and Arizona, however, allow jurors to ask witnesses questions in writing.

Juror questioning is generally more accepted in civil trials than criminal ones, although long, complex cases full of unfamiliar legal terms and expert testimonies may. some scholars argue, benefit from the application of juror questioning. Supporters believe that juror involvement is essential to any fair trial, since misunderstandings can be clarified quickly, jurors are more likely to pay attention to proceedings, and the jury's confidence in reaching a just verdict is enhanced.

Critics, meanwhile, worry that juror questioning affects the constitutional right of the accused to a fair trial. If jurors interrogate witnesses, they begin to take on the role of the advocate, which undermines their neutrality as jurors. Other commentators also argue that questioning delays proceedings, especially when jurors ask confusing or inappropriate questions.

Several cases in which juries have asked questions have had their decisions overturned. In 2000 Judge Ann Marie Tracy authorized jury questioning during a burglary trial. The conviction was overturned by the Ohio First District of Appeals on the grounds that even written appeals from jurors endangered the jurors' neutrality The Ohio Supreme Court later upheld the right of judges to allow juror questioning, stating that "History has ... relegated the jury to a passive role that dictates a one-way communication system. The practice of allowing jurors to question witnesses provides for two-way communication through which jurors can more effectively fulfil their fundamental role as fact finders."

Juror notes have also been a question for debate. Some judges disallow them since they believe that notes distract jurors from testimonies, and that deliberation could be unfairly dominated by jurors with extensive records. But supporters argue that the benefits of giving jurors the means to keep track of key evidence outweighs this objection.

The following articles examine the debate in further detail.

Keeping A Jury Involved During A Long Trial

Harold J. Bursztajn et al.

Harold Bursztajn is a psychiatrist and associate clinical professor and codirector of the Program in Psychiatry and the Law at Harvard Medical School. He treats patients and testifies as an expert and trial consultant. Linda Stout Saunders is president of the New Hampshire Trial Lawyers Association. Archie Brodsky is a senior research associate with the Program in Psychiatry and the Law at Harvard.

Presenting complex, unfamiliar evidence to a jury in a long trial in which emotions are running high is a formidable task. When jurors hear a case that stretches over weeks, even months, they often become bored and resentful, making them especially susceptible to falling back on their preconceptions and prejudices. Combine these emotions with a sense of fear and helplessness about going through such an arduous process, and lawyers can foment this mixture into desires for revenge against the defendant, the prosecution, or, as may have happened in the O.J. Simpson case, against law enforcement and social ills sucli as racism.

Problem of bored jurors

Isolation from loved ones and well-known surroundings results in jurors creating a safe mental environment, especially when exposed to complex evidence that can appear threatening by its very unfamiliarity. Thus, when jurors retreat from the boredom of a long, complex trial by daydreaming or dozing off, they hear the evidence through the filter of their own memories, fantasies, and dreams. For example, psychosis is unfamiliar to most people, so in an insanity defense case, jurors typically re[latc to] the familiar experience of being sane, discounting the feasibility of insanity. When complex DNA evidence is introduced in a trial where race is an issue, jurors may fin[d their] own experience of discrimination based on the factor of skin color to be the most salient point [by] which to make their judgments.

Of the various reforms proposed, such as not sequestering [1] juries, limiting the use of peremptory challenges, barring television cameras from the courtroom, and shortening the duration of trials, it makes more sense to as[k how] the jury's time can best be used. The most promising reforms are those that would involve the jurors as active responsible participants. One suggestion is to allow juries |fo| ask questions of the trial witnesses.

In medicine, the patient's participation in a dialogue with the physician has been recognized as a valuable [part] of the decision-making process. Dialogue is also the [method] of group psychotherapy. A successful medical mode [that] could translate to the courtroom is the group therapy [pro]grams that are used in treating those addicted to self limiting or self-destructive lifestyles. These individual[s are] largely resistant to preaching about the evils of. say alcohol, but they do benefit from an interactive approach [that] confronts their own preconceptions.

As an example, individuals who have been drinking heavily for years often have atrophied [2] problem-solving skills. In the group therapy session, the group leader elicits each individual's prejudices without endorsing them. If someone says, "Being drunk makes me a better driver," the leader asks how that is so. The person may then explain that without alcohol, he or she becomes so preoccupied by personal problems as to be distracted and over-anxious behind the wheel. The leader then asks, "Is there any other way besides drinking to keep yourself from getting so preoccupied? Does anyone else have any suggestions?" In time, the group members take over more of the work from the leader and build a fund of shared experience that becomes familiar, so that they can draw on it for alternatives to their former beliefs and habits.

Drawing on shared experience

It's likely that juries, too, would deliberate more effectively if they could draw on such shared experience in problem solving. Deliberation is a public interchange—an airing of hypotheses and conclusions in the corrective light of social reality—and not just a silent consultation with one's personal beliefs, feelings, or ideals. But how can jurors engage one another in deliberation if they have been sitting passively for months, as the Simpson jury did? [3]

To set the stage, the jury must be actively involved in the trial itself. The machinery already exists in the practice of allowing jurors to question witnesses through the judge. The Federal Rules of Evidence (Fed R. Evid. 614(b)) [4] establishes the right of a federal trial judge to question witnesses, and federal and state courts have held that it is within a trial judge's discretion to permit questions from jurors. Judges in at least 30 states are soliciting written questions from jurors and posing them to witnesses after screening them with the lawyers from both sides.

|

| O.J. Simpson and his defense team in court after his not guilty verdict was announced on October 3, 1995. This high-profile trial has led to proposed reforms in the trial system, including allowing jurors to submit questions in order to clarify issues. |

Some legal observers urge that this procedure be more broadly utilized. Studies by the American Judicature Society, the State Justice Institute, and other organizations [5] have shown that allowing jurors to ask questions keeps them alert, focuses their attention on relevant issues, and enhances their sense of participation and responsibility. Judges find these benefits especially clear in complex cases.

Hot to cool decision-making

By encouraging jury involvement, the judge can help the jury move from "hot" to "cool" decision making, a term coined by psychologist Irving Janis. [6] Hot decision making is driven by the passions of the moment; people grasp for instant solutions to relieve emotional pressures and conflicts among themselves. Cool decision making is fostered by openly addressing uncertainty and talking out the issues.

Trial lawyers sometimes seek to stimulate hot decision making, such as when the prosecution plays on the jury's sympathy for crime victims, or, as in the case of O.J. Simpson; when the jury appears to identify with the defendant as a fellow prisoner in the long trial. But when the judge allows jurors to be more than silent observers, and refuses to yield control of the case to the lawyers, the judge can control the heat of the decision making by the tenor of his or her questions to witnesses as well as by guiding the jurors questions. The judge engages jurors in a dialogue, demonstrating by example how they can question not only witnesses, but also each individual juror's personal beliefs and prejudices.

When jurors are invited to ask questions, their concerns and uncertainties can be addressed. Through the leadership of the trial judge, the jurors can explore alternative ways of understanding the grains of truth around which prejudices coalesce. Although trials will never in and of themselves be therapeutic, trials in which jurors participate actively will have the potential for healing rather than exacerbating the divisions in our communities. [7]

The Current Debate on Juror Questions...

Nicole L Mott

Dr. Nicole L. Mott is a research associate at the National Center for State Courts in Virginia.

... As stated in an opinion by the Supreme Court of Minnesota, courts are concerned with the effect juror questions may have on due process. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Blatz stated that "[t]hose who doubt the value of the adversary system or who question its continuance will not object to distortion of the jury's role."

Concerns about the drawbacks of jury questioning are suggested by the "cautionary instructions" adopted by many states and identified in the ABA standards. [8] The ABA standards enumerate several points for courts that choose to implement the procedure. For instance, juror questions ought to be used only for important points and clarify testimony. A concern for how juror questions may transform the juror's role is also apparent. Jurors "are not advocates and must remain neutral fact finders." Further instruction is given to clarify why some questions may not be asked, for instance, due to evidentiary rule objections or interference with litigation strategy.

The juror's role and questioning

The main concern with implementing this procedure is that through questioning a juror may lose his or her neutrality and become an advocate. [9] But whether a juror's role would change is difficult to ascertain. If a juror's role is similar to that of the judge, what precautions do judges assume when asking questions? A notable difference is that judges are trained in the law and legal procedure. However, any juror question is subjected to scrutiny by the judge as well as both counsel. Critics voice one concern of the potentially negative effect on the jury if an attorney were to raise an objection. Heuer and Penrod's study [10] did not find that counsel was reluctant to raise objections to questions. [T]hey found jurors were not angry or embarrassed when the objections were sustained. In fact, in the Wisconsin trials, jurors typically reported they understood why their questions were not asked.

A common comparison typically used to evaluate the reasonableness of a jury's verdict is whether or not the judge agrees with it. Heuer and Penrod employed this technique to assess any effect on jury verdicts in trials allowing jurors to question witnesses. They concluded that judge and jury agreement rates did not differ between questioning and nonquestioning juries. Agreement rates were determined by comparing the jury's verdict and the judge's hypothetical verdict. Judges were asked to determine what verdict they would have reached in a bench trial. As a further comparison across experimental trials, the verdicts reached by questioning juries did not differ from those that were unable to question witnesses.

How jurors perceive attorneys

Another concern voiced by critics of juror questioning is that jurors will prematurely begin to accept one counsel's hypothesis over another's. This argument suggests that when jurors frame a question they are testing a hypothesis. However, jurors in Heuer and Penrod's study were asked whether they perceived one attorney less favorably than another, which would occur if the jurors had lost sight of their neutrality. In actuality, jurors perceived both attorneys more favorably in the trials that allowed questions than in those without the procedure.

Critics of jury questions also argue that jurors will disproportionately weigh the answers to their own questions. [11] However, when jurors were surveyed, they reported an average of fifteen minutes—or 10% of their deliberations—were spent discussing such answers.

What attorneys fear

Logistical issues surface among critics of the procedure, primarily among attorneys. Attorneys have expressed concern that jury questioning will alter the strategic plan of how the evidence is presented. However, attorneys who have experienced jury questioning did not encounter these problems. Videotaped testimony creates another logistical concern. [12] For example, jurors would be unable to ask questions of witnesses who testify via videotape. In a Missouri case, the court ruled that jury questions were unfair in trials presenting videotaped testimony.

However, with basic recommendations for implementing jury questions, several concerns are allayed. For instance, the flow of the trial is only disrupted when the questions are not properly managed. Most guidelines suggest that jurors submit their questions in writing after the completion of testimony by a witness. Attorneys have also expressed concern about how a juror is told his or her question will not be asked.

|

| Domestic diva Martha Stewart, one of America's most successful businesswomen, during her obstruction of justice trial in May 2004. During the trial jurors were allowed to ask questions of Stewart via the judge. Stewart and her codefendant Peter Baconovic were found guilty. |

There is no evidence from empirical [13] studies that this is a concern. If the judge instructs jurors that questions may not be asked in open court due to the rules of evidence or an attorney's trial strategy (e.g., the question will be answered at a later time), it is unlikely jurors will misinterpret this ruling as revealed in findings from the Heuer and Penrod study.

Possible delays

Attorneys, judges, and court managers are concerned that the benefit created by allowing juror questions does not outweigh the burden created as a result of the time delay that would occur. This argument is based on an assumption that jurors will ask numerous, and possibly unreasonable, questions. The study in New Jersey found that the estimated median time added to trials allowing questions was only thirty minutes. [14] Furthermore, the assumption that jurors will be unyielding and unreasonable if provided the opportunity to ask questions is unfounded. A study asking judges in Arizona to rate the reasonableness of juror questions found that judges' ratings were extremely high.

Despite this evidence, some courts have been expressly critical of allowing juror questions of witnesses. In one notable case, an Ohio appellate court ruled, "the practice of questioning by jurors is so inherently prejudicial" that there is no need to demonstrate the prejudice specifically. The thrust of this opinion is that the juror's role is transformed once the juror begins interrogating witnesses, so the juror is no longer a neutral decision maker. Among opinions critiquing juror questioning is the oft-cited opinion of Judge Lay proffering that juror questioning promotes a "gross distortion of the adversary system."... [15]

Summary |

The question of whether jurors should be able to participate more actively in trials has been debated for centuries. In the first article Harold J. Bursztajn, a clinical and forensic psychiatrist, Linda Stout Saunders, president of the New Hampshire Trial Lawyers Association, and Archie Brodsky, a senior research associate at Harvard University, argue that jurors often get bored and restless during long, complicated cases that makes them more susceptible to biases and prejudices. They argue that more active jury participation helps the process by keeping jurors alert and focused. Asking questions, in particular, the authors contend, makes a juror more likely to listen to testimonies and stay focused on the issue at hand. Bursztajn and his co-authors assert that "Through the leadership of the trial judge, the jurors can explore alternative ways of understanding the grains of truth around which prejudices coalesce." In the second article Nicole L. Mott, a court research associate of the National Center for State Courts, addresses the concerns many commentators have about increased juror participation. Mott quotes Chief Justice Blatz, who stated that "[t]hose who doubt the value of the adversary system or who question its continuance will not object to distortion of the jury's role." Mott points out that the American Bar Association's juror-questioning guidelines are "cautionary" ones, warning that any questions asked must not infringe on juror impartiality, the primary worry about juror-questioning. Another concern is that juror questioning can cause delays if jurors ask numerous, possibly unreasonable questions, and this affects the cost of the trial. |

Further Information:

Books:

Abramson, Jeffrey, We,

the Jury: The Jury System and the Ideal of Democracy Cambridge,

MA Harvard University Press, 2000.

Hans, Valerie P., Neil Vidmar, and Hans Zeisel, Judging

the Jury. New York HarperCollins, 2001

Useful websites: http://www.abanow.org/2010/03/faqs-about-the-grand-jury-system/

American Bar Association FAQs about grand jury system

http://www.juryinstruction.com/article_section/articles/article_archive/article43.htm

2002 article by Thomas Lundy outlining the advantages and disadvantages

of juror questioning

http://www.supremecourt.ohio.gov/PIO/summaries/2003/0611/020201.asp

Article on the 2003 Supreme Court ruling that juror questioning is within

the discretion of a trial court

- "Sequestering juries" means secluding or setting them apart. "Peremptory challenges" are challenges that a lawyer has a right to make.

- "Atrophied" means wasted away or deteriorated.

- The 1995 criminal trial of O.J. Simpson for the murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman lasted 133 days. Simpson was found not guilty. Go to http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/simpson/jurypage.html for analysis of the Simpson trial jury.

- The Federal Rules of Evidence govern the introduction of evidence in civil and criminal cases in federal courts.

- Go to http://www.nlrg.com/our-services/jury-research-division/jury-research-publications/gaining-an-edge-in-jury-trials/ for information about research by the National Legal Research Group into techniques designed to make jurors more involved in the legal process.

- Irving Janis (1918-1990) was a research psychologist at Yale University. He is famous for his theory of "groupthink" which described the systematic errors groups make when coming to collective decisions.

- Do you think that the author's suggested use of techniques from a therapeutic context is appropriate for a court of law? If not, why not?

- The American Bar Association (ABA) Criminal Justice Standards have guided law policymakers and practitioners since 1968.

- In your opinion is the neutrality of jurors jeopardized by their asking questions?

- Larry Heuer and Steven D. Penrod's study "Increasing Juror Participation in Trials through Note Taking and Question Asking" was published in 1996.

- If you were a juror, do you think you would pay more attention to the answers to yoru questions rather than to those of other jurors?

- Videotaped testimony is used in court when witnesses are unable to attend because of physical or mental incapacity. Children often testify by this method. Counsel can edit and present videotaped testimony if it will assist the jury in understanding evidence or the relevance of a particular issue.

- "Empirical" means based on observation or experience.

- Is 30 minutes an unreasonable amount of time to be added on to the length of a trial if juror questioning is allowed?

- Judge C.J. Lay made this comment during United States v. Johnson in 1989. Despite Lay's criticism of juror questioning, the case failed to establish a rule totally banning juror questioning of witnesses.